My memories of childhood vacations in the station wagon with my brother and sister are punctuated by stops along the highway to read the historical markers. We read them all. Before we could read them, Mom and Dad read them to us. I am now afflicted with the irresistible, visceral need to read every posted sign I pass. I laugh at myself, but it seems to me that a culture puts into words what it deems vital.

The names of city streets are a good example. Here is a street named for a Breton poet. In the Reuilly suburb of Paris we traversed this street named for a local firefighter who gave his life fighting a neighborhood fire.

Roads are labeled more

prominently by the next town than by the road number; during the Occupation in the 1940s, residents in France (and England as well, in anticipation of an invasion) moved or removed the signs to confuse the enemy.

French towns welcome visitors and note their boundaries with a pair of signs, coming and going. Notice that the name of this village in Cantal, near Aurillac, is in Occitan, not French. The universal use of

French dates to World War I, when the Alsacian, the Breton, the Provençal, and the southern boys who spoke Occitan gathered in one army. Those that went home spoke French, and after the war, government activities and education nationwide were conducted in French. This sign is written both in Breton and in French. The regional languages are rarely spoken in the home as a native language, but are still available to be learned in schools.

In the country, addresses are not numbered on roads but named. Cavalhac is the name of the farm of the Ginioux family near LaCapelle del Fraisse which is in the Cantal. The nearest city of Aurillac is nestled in the river valley, a charming place.

The coastal path that follows the Breton coast is marked with various stripes of color denoting a lengthy hiking path or an easy local trail. After Jean-Jacques explained the system to me, I began to see the little stripes on posts and trees, marking turns and intersections.

This is not really a street sign, but rather a parking sign that I found delightful in its guilt trip: if you take my parking place, take my handicap, too. That almost amounts to a curse, doesn’t it? Do you suppose it is more effective than the chair alone?

Building signs

often have a story to tell. In Sevilla I was astounded to find the location of the original Carmen. Her tobacco factory still stands, with the name a part of the art that the casual visitor might pass without seeing. In Paris, the Orsay museum tells the story of its role post-war in the care of the survivors of the prisoner of war camps and the death camps of Eastern Europe. At the time, this building was the central train station in Paris; from April to August of 1945 when the gaunt and nearly dead victims of the camps arrived, they were simply too ill to go any farther, so the station was converted to a hospital. It became the largest repatriation center in the country. It is a solemn testimony to those who so suffered that this moment in the Orsay history be publicly remembered, even as the building takes on such a completely different role as the impressionist art museum.

This historical marker in the park on the far east side of Paris seems almost to miss the good old days when the neighborhood had a more illustrious life. A garden in the heart of the Left Bank honors Saint Catherine Labouré, the nun whose vision of the Virgin Mary led her to create the Miraculous Medal. Saint Catherine is enshrined in the adjoining chapel, which is daily thronged with pilgrims.

Store owners use this common sign to reassure clients that they are permitted to browse in the boutique, as the custom for small shops is that clients do not enter until they have selected their purchases from the window display and are ready to buy.

Governments have used signs to persuade the populace: this British poster from the 1940s uses the heroic and sacrificial leadership of Joan of Arc to inspire the women to save Britain. This sign in Hemmerde, Christian’s home, celebrates the communities’ long life.

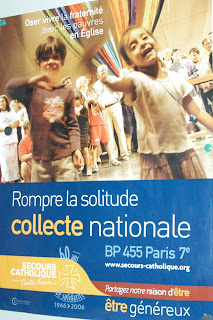

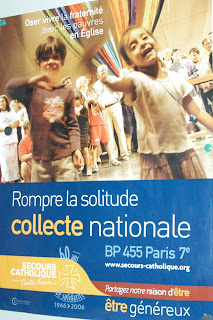

In today’s Paris, the mayor’s office reminds citizens of their civic duty by commending them for their solidarity and urging them to aid their neighbors, an inspired means to urge a diverse populace to seek common ground. This

notice in the Saint Denis cathedral on the far

northeast side of Paris asks visitors and parishioners alike to give generously of what they have, to care for each other. The prominent displays of this hostage taken in Columbia and her status as an adopted Parisian also asks the populace to be globally aware, reminding us that we are all citizens of the world. What a commendable way to inspire international collaboration!

Along the Breton coast there is a windswept cliff with a small

stone cabin, once a key coastal defense position. This poignant sign asks passersby to remember the role of this place in protecting the populace from the all too frequent threat from the sea. The name of this boat is Son of the Wind, a delightful irony as Jean-Jacques had just told me as me walked along the quay leaning into the wind of a time that he had been blown horizontal, hanging on to some rail for dear life.

On our trip to Finistère, Jean and Marie-Claire and I stopped to read this sign on the monument marking the site of the devastating shipwreck of the Amoco Cadiz in 1974. The ship spilled crude oil that became a black tide for Brittany, whose economy depends heavily on fishing and tourism, both of which were virtually eliminated for a costly period of time. The cost to sea life was greater, killing birds and sea animals in appalling numbers.

This memorial on the point above the little port beside the Val-André commemorates Breton sailors lost at sea. Briac is doing his best to explain what that means to a child of this land bounded by the seas.

In the cathedral dedicated to her memory, built high on the hill above her native village, Joan of Arc’s final words are written under the murals that depict her life. “I declare once again, my voices were from God, no, no, my voices were not mistaken... Jesus! Jesus!”

And at the entrance to the chapel dedicated to the soldiers who gave their lives for France are Joan’s words to her countrymen on behalf of those patriots: “Build chapels to pray for those who gave their lives for their country.”

Her home town of Domrémy has been renamed in her honor, using her nickname, La Pucelle. In the church where she first heard the voices of the saints, the statue of Ste Marguérite has been removed due to a near theft; its location is now marked with this plaque.

It is

the signs that bestow honor on those who lay down their life for their country that speak most powerfully to me. They appear frequently in Brittany, Normandy, Paris, Lyon. This plaque in Lyon honors the memory of the 300 students who died in the resistance; another marks the place of the execution of 7 young men, young Jews. In Ploubelay, near Saint Mâlo, this sign marks the spot of another French soldier’s death, August 6, 1944, but the plaza is named for an American who died here August 7. In a carefully selected proximity to these signs is the notice of the town’s sister city, in Germany.

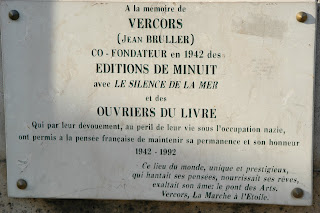

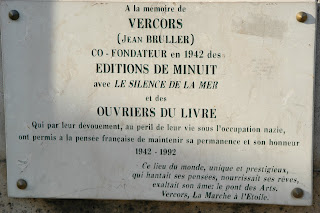

In Paris this bridge honors those who printed and distributed the clandestine press during the

Occupation. In Cantal with Berndette, we stop in the village church of Lacappelle del Fraisse where I see the children’s uncles listed on the wall plaque. Everywhere there are war memorials, but here in St. Mâlo I find the list of civilian deaths longer than the regular army or the resistance. In Saint Pois as well there are civilian deaths listed as victims of the war, across the nave from the list of military dead.

Both these coastal towns bore the heavy blows of the invasion.

Outside Saint Pois along a remote country road, we find the Brittany American Cemetery, one of many that dot the countryside, carefully groomed and maintained, mute

testimony to the honor in which

they are held. Listening in this place, the accents I hear range from Texas to Boston to Georgia. These young Hoosiers heard and answered the call of their country. Their sacrifice is not forgotten and continues to

uphold the sense of brotherhood that the French people express for Americans. There is no politics in that sentiment, only a recognition of having shared the brutal agony that bought our freedom.

The University classes finished Friday at 4pm so that the summer students could gather for a reception where grades were distributed. Unfortunately, in order to get to Paris early enough for an international flight, I had to skip the reception and the last meeting of the Written Argumentation class. I did 3 hours of homework the night before to make up for my absence, a summary, an opening argument, and an imitation of a satirical essay. The class apparently did little of that, so my absence was productive.

The University classes finished Friday at 4pm so that the summer students could gather for a reception where grades were distributed. Unfortunately, in order to get to Paris early enough for an international flight, I had to skip the reception and the last meeting of the Written Argumentation class. I did 3 hours of homework the night before to make up for my absence, a summary, an opening argument, and an imitation of a satirical essay. The class apparently did little of that, so my absence was productive. The subway from the University to the Rennes train station was a matter of minutes, and the train to Paris is smooth and rapid. There is another train directly to the airport, where the security is meticulous. I was in Sevilla before dark, met by my French “sister” Christine, whose family hosted me in 1969. She went to Spain for her Master’s Degree in Spanish, married Eusebio, a Spanish lawyer, and stayed to become a French teacher. Her children, Eubsebio and Alexandra, are the age of mine. The network of our families is closely tied across 3 generations. Their Papa

The subway from the University to the Rennes train station was a matter of minutes, and the train to Paris is smooth and rapid. There is another train directly to the airport, where the security is meticulous. I was in Sevilla before dark, met by my French “sister” Christine, whose family hosted me in 1969. She went to Spain for her Master’s Degree in Spanish, married Eusebio, a Spanish lawyer, and stayed to become a French teacher. Her children, Eubsebio and Alexandra, are the age of mine. The network of our families is closely tied across 3 generations. Their Papa  is dear to me, my parents stayed with them for a month the year of the 500 anniversary of Columbus voyage to America.

is dear to me, my parents stayed with them for a month the year of the 500 anniversary of Columbus voyage to America.

I spent a weekend of relaxing, shopping, and girl talk. After a Friday evening thinking that this would be a vacation from the working photographer seeking every highlight to use in class, I suddenly realized with Christine’s reminder that my son is now a Spanish teacher, so I snapped back into high gear. We walked through a former palace, now an elegant hotel. The

I spent a weekend of relaxing, shopping, and girl talk. After a Friday evening thinking that this would be a vacation from the working photographer seeking every highlight to use in class, I suddenly realized with Christine’s reminder that my son is now a Spanish teacher, so I snapped back into high gear. We walked through a former palace, now an elegant hotel. The

mosaics are simply stunning. The Arab influence is very visible, blending with the Spanish art to create a breathtaking city. Many bridal choose the Alcázar palace with its treasures of art and gardens. My Sevilla photos are limited since we did little touring, but this photo of

mosaics are simply stunning. The Arab influence is very visible, blending with the Spanish art to create a breathtaking city. Many bridal choose the Alcázar palace with its treasures of art and gardens. My Sevilla photos are limited since we did little touring, but this photo of

ladies resting

ladies resting in the shade on the Plaza of Spain is perhaps my favorite photo as art. Each region of Spain has a mosaic and a map in a magnificent public display created for the World’s Fair. Maintenance of this public art is becoming increasingly urgent and expensive. Christine and Chebi are family in

in the shade on the Plaza of Spain is perhaps my favorite photo as art. Each region of Spain has a mosaic and a map in a magnificent public display created for the World’s Fair. Maintenance of this public art is becoming increasingly urgent and expensive. Christine and Chebi are family in

many ways, including the addiction to owning books. The view from their balcony at night is splendid, but so is the view in every room of bookshelve beckoning the avid reader! Fortunately many are in Spanish, which reduces the temptation.

many ways, including the addiction to owning books. The view from their balcony at night is splendid, but so is the view in every room of bookshelve beckoning the avid reader! Fortunately many are in Spanish, which reduces the temptation.